The boutique segment of the executive search business is growing like never before. With the economy improving and large firms rebooting, talent management clients are becoming more accepting of specialists running their search assignments. In fact, they are driving the trend. These smaller, more intensely focused independent recruitment providers, concentrating on just one or two business sectors or a handful at most, are redefining a field once dominated by a handful of large, generalist players. And as social media technology advances, these new-age ‘preferred providers’ are better equipped than ever to take on their larger rivals. They promise more attention to client’s needs. They tout themselves as more nimble and flexible. And they are often staffed by recruiters who learned the trade at the big firms. A common refrain is that boutiques bring the best of both worlds: big firm training and small firm personal dedication.

The causes for this change are varied. In-house recruiting initiatives are clearly driving a vast realignment in the talent field. Surveys conducted by Hunt Scanlon Media suggest that the move ‘inward’ by companies to recruit workers is costing the search industry more than $600 million in fees annually, a figure expected to increase in the coming decade. Boutique firms that can prove their proficiency in handling unique and difficult-to-fill assignments are the ones now in demand. Inside the search business, those drawn to boutique firms are entrepreneurs who would have started their own operation under any circumstances. Some, too, are former employees of the big firms who simply grew weary of bureaucracy and a business model that rewards business development prowess over assignment execution skills. The new breed of independent recruiter professes to be both salesman-in-chief and lead recruiter, all served up with high touch service.

Specialization is a big part of the appeal of the boutique search provider. As big firms have expanded, with some now publicly-traded, feeding the bottom line has naturally become a paramount business concern. The boutiques, meanwhile, have more leeway to concentrate on getting to know the ins and outs of any given sector, giving them perhaps a leg up on better understanding the culture of their client companies. Fit, these recruiters say, has become the new mantra, with cultural sensitivity triumphing a candidate’s skill set. These search specialists say they are uniquely qualified to be more responsive to these new requirements. The more established, top branded firms have always been the safe choice, especially when a prominent company is changing leaders or upgrading its leadership team. But that’s changing. As more heads of talent acquisition and those in charge of corporate search committees give the boutiques a chance to handle their most sensitive searches, those at the C-level, the floodgates have opened.

Never in the history of executive search have there been so many boutique firms setting up shop. In the U.S., the recruiting industry’s dominant marketplace, Hunt Scanlon Media has identified and now tracks more than 3,000 retained search firms. What’s most striking: 25 percent (750) have formed in just the last seven years. They generally range in size from five to 10 consultants, but many have formed with just one to three recruiting professionals onboard. Outside the U.S., a similar burst of boutiques launching their specialty brands can be seen. With most of the world’s economies on the march again, companies are inking employee contracts after more than a half decade of hiring stagnation, and they are turning to this exclusive group of service providers much more vigorously than they did before the Great Recession.

The Great Recession

The trend toward specialization dates back to the 1990s when the dot-com explosion served up a massive new search sector for the recruiting business. Savvy search consultants at larger firms eager to cash in on the enormous hiring boom started to break away, ready to plant their own flag. Other solo practitioners combined forces and joined the fray. But it was the 1999 search for a successor to Lewis E. Platt, the chief executive at Hewlett-Packard Co, that sent the signal that something big was underway in the insular world of executive recruiting. The giant Palo Alto computer maker turned away from its big brand recruiters to hunt for Mr. Platt’s successor – likely due to off-limits restrictions that would have prevented them from luring talent from H-P’s direct rivals – and instead hired Cleveland-based Christian & Timbers, an upstart technology-oriented search boutique that was dominating search work in Silicon Valley. Jeffrey E. Christian, the firm’s founder, had cracked the door wide open. He vanquished the industry’s acknowledged powerhouses. Mr. Christian was quirky and brash – he was a tireless self-promoter and he did the search work himself. He set the standard for all the boutique players that were to come. But the boom ended in a crash and Mr. Christian’s firm faltered, as did a number of his small firm rivals. There was a bit of a rebirth of boutiques in 2003 but that was also short- lived: a second, more severe downturn starting in 2007 sent the entire search industry flatlining and for boutique firms it was once again a time to scale back.

In-House Recruiting Takes Root and Takes Off

Out of the retrenchment period of the Great Recession came the corporate mandate to cut costs. Talent acquisition professionals at blue chip companies known for their progressive hiring strategies and bloated search budgets were tasked with developing innovative ways to limit what they spent on recruiting talent. At large concerns staffing budgets were cut by tens of millions of dollars annually – but, somehow, quality of hire was to be maintained. Over time, ‘quality of hire’ trumped the financial pressure to cut ‘cost to hire’ and thus began the great migration away from using search firms as the primary way to recruit talent.

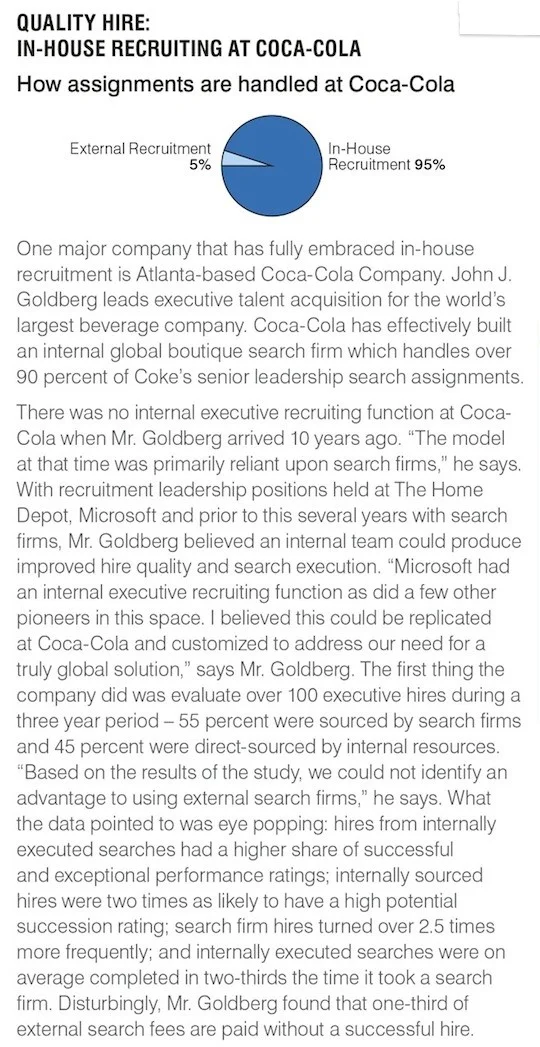

John J. Goldberg, head of executive talent acquisition at The Coca-Cola Company, says that cost containment was not the primary driver for Coca-Cola to bring more of the company’s senior-level recruiting function in-house. “Our starting point was delivering the highest quality hires and how to execute against the most challenging search assignments,” he says. “Cost savings are another important benefit – but frankly if we had to pay more to get higher quality hires we would. It just turns out that it’s the other way around.” Mr. Goldberg says that off-limits problems have compromised the field of talent available to external recruiters – and those caught in the off-limits quandary are now the specialist boutiques themselves. “The irony is a common rationale of using a niche firm is that they know everybody in their space, but if they do and are successful placing them then their potential talent pool is reduced by off-limits constraints. In that respect I believe they are apt to have the same limitations some of the largest firms often have.”

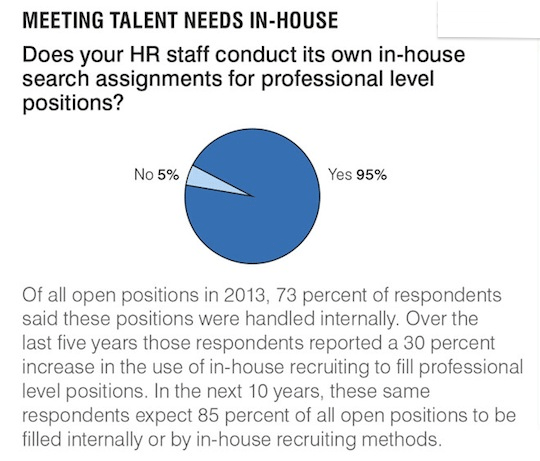

Growing numbers of talent acquisition professionals are acutely aware of this and firmly believe that taking control of the search process internally will infinitely expand their candidate universe. “By handling the process ourselves we have unconstrained access to the global talent pool,” says Mr. Goldberg. The trend to go ‘in-house’ is advancing: 95 percent of talent acquisition professionals surveyed for this report now use in-house recruiting methods to fill at least some professional level positions. In the next decade these respondents predict that 85 percent of all open positions will be handled without the use of an outside executive search consultant; those positions they do send out to be filled externally will likely be handed to a boutique specialist. (See related Exhibit 1: ‘Meeting Talent Needs In-House’).

Exhibit 1:

The Coca-Cola Company operates in 207 countries globally and has an employee population that is almost evenly dispersed around the world. As such Coca- Cola has the need to execute search assignments in both developed and developing markets. “Search firm capability is stronger in larger more developed markets, less so in developing markets and for global search assignments,” says Mr. Goldberg. “As our needs are broader, we developed a function that is uniquely equipped to handle these types of assignments. We need to be just as effective on an assignment in Sub-Saharan Africa as we would be for Western Europe, and be able to execute searches effectively both locally and globally for these roles.”

Since the Great Recession, companies like Coca-Cola – Nike, Sears, eBay, Allstate, PG&E and infinitely more – have all turned inward, setting up some unusually sophisticated hiring programs. And while much of their in-house recruiting initiatives focused on middle management positions early on, today more than 90 percent of talent acquisition providers believe they can recruit any level of talent from internally-sourced resources. (See related Exhibit 2: ‘Quality Hire: In-House Recruiting at Coca-Cola’)

Exhibit 2:

Boutiques Become ‘Preferred Providers’

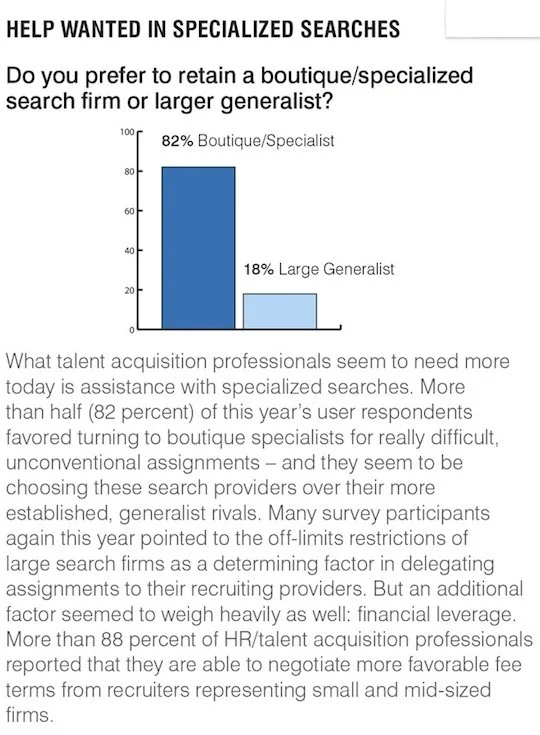

In-house recruiting is not a new concept but its broadening development and the reasons behind it are causing alarm and anxiety in the executive search industry. Indeed, many recruiters say the changes that have been wrought out from the Great Recession are permanent. And while Coca-Cola’s Mr. Goldberg sees growing trade-offs in using search firms of any size, many others in the talent acquisition field say the ultimate winners of in-house recruiting initiatives are the boutiques. They are the firms with proven track records at finding the diamonds in the rough – those difficult-to-fill, time consuming searches for specialized leaders. (See Related Exhibit 3: ‘Help Wanted In Specialized Searches’)

Exhibit 3:

Seemingly at odds with this trend to spend less time and money with external search providers is the exponential growth taking place in the search industry itself. In each of the last three years the recruiting industry in the U.S. has enjoyed a nine percent annual growth rate. How can this be if companies are slashing their use of these talent providers? The largest recruiting outfits have been expanding their base of business, with good success. Companies may be spending fewer dollars to recruit for individual positions but they are spending more for ancillary human capital services like assessment and leadership development. That’s largely been behind Korn Ferry’s staggering 20 percent growth rate in its U.S./Americas region and globally this past year. But as boutique specialists become the de facto ‘preferred providers’ for companies doling out fewer search assignments, they are also the ones reaping more fees. Boutique recruiters generally are growing, in many cases, by double digits.

“Part of this activity is the result of a natural business cycle,” says Larry Ross, president of Ross & Company, a Boston-based search boutique. Having worked for Russell Reynolds Associates and Korn Ferry, Mr. Ross left the big-firm environment to start his own in 1992. He suspected that the financial services industry was poised to flourish and his bet paid off. But what Mr. Ross failed to anticipate were the other pluses of going out on his own. “We weren’t just filling positions for our clients, but we were becoming a more trusted advisor.” Now, Mr. Ross and his partners can devote more time and attention to understanding the culture of their client companies. “That was not necessarily the case with the larger firms I worked with,” he says.

A Niche Search Firm Stands at the Ready

For all the boutiques that started in the 1990s, the greatest explosion has come more recently, post-recession. Over the last few years, more solo practitioners and small groups of consultants have been starting their own firms, either as spinoffs from larger firms or as startups. (In an accompanying section to this study, it is reported that women are launching a large percentage of these newly created entities). Ironically, much of this trend has to do with the recent growth of the bigger firms and their changing internal cultures. In years past, even the largest search firms maintained an entrepreneurial environment, which empowered recruiters. But the growth that the big firms have seen over the last three years began to undermine that. There’s been a sudden shift in spirit and focus, say recruiters who have departed. Today, Korn Ferry is approaching $1 billion in revenue – a symbolic benchmark, these recruiters say, that the ‘small firm feel’ is now dead or dying and many recruiters have been left to find that kind of intimate culture on their own.

James J. Carpenter is a case in point. Having spent 20 years as a top consultant at Russell Reynolds Associates, leading the firm’s global consumer sector and launching its chief marketing officer practice, Mr. Carpenter had grown tired of the big firm atmosphere. “Russell Reynolds is a great firm and I enjoyed my years there,” he says. “But the culture was changing as were the dynamics – and the entrepreneurial spirit was becoming lost.” He points to a big problem that many of the top firms are facing today: senior recruiters taking on far too many assignments as the industry, and top level hiring, rapidly expands once again, causing a quality void. “The challenge for seasoned consultants is that they want to take on the work and satisfy their clients, but in order to accomplish this they have to pass the work on to more junior associates who today are more ‘junior’ than ever,” he adds. “They are not being trained as well as they once were and in the end the client loses out.”

In 2009, Mr. Carpenter left Russell Reynolds to form J. Carpenter & Company, which is based in Darien, Connecticut. Although Mr. Carpenter has a smaller client load than he had in his old job, he feels he is serving his clients better. “I personally work on every assignment and they have my full attention,” he says. “I know every detail from the largest to smallest component and my clients are extremely content with me.” Truth be told, he’s more content himself. “The quality of my life has improved dramatically,” he says. “Instead of commuting to New York from Connecticut each day, my office is just a 10-minute drive away from home and I’m working in a small, fun, and exciting environment with three great people. That’s an element that doesn’t show up on paper but it’s real and if I’m happier it benefits my clients.”

Scott Miller is another recruiter who was looking to heighten his passion for his work. Having served as a client partner in Korn Ferry’s education, diversity, and association specialty practices, Mr. Miller was finally ready for a change. Nine years of life at the big firm, he decided, was enough. “While my years at Korn Ferry were beneficial, I felt that in order to have a deeper conversation with clients I needed to be on my own,” he says. So it was that in 2009 Scott Miller Executive Search, a non-profit boutique which recruits development directors, was born. Now, in the trenches every day, Mr. Miller felt he was getting close to his clients in a way that was impossible before. “There is no greater degree of connectivity in a smaller firm environment and that comes from the client, too,” he says. “They tend to feel that I have more ownership in the process because I’m focusing in on just their search, not a dozen others at once.”

Dave Arnold of Los Gatos, California-based Arnold Partners also sees a trending toward specialization and in clients being more accepting of boutiques than they had been in years past. “It used to be that the large search firms would get many of the higher-level assignments because they had the name recognition and that brand denoted a safe choice,” says Mr. Arnold, whose firm specializes in CFO assignments for Silicon Valley companies. “Today clients are far more sophisticated,” he says. “They know we can do as good a job. We are far more nimble and creative and that has far wider appeal today because those elements are more essential as the positions we are filling are more complex.” Mr. Arnold, who launched his firm in 1998, during the dot-com boom, sees one more critical differentiator: “Today more than ever, search is about accountability. If you work for a large firm you may not take as much ownership in a relationship. For consultants like us, the buck stops here. Our name is the one on the door.”

Hunting For a Special Breed

Nowadays, finding top talent goes beyond mainstream industries like financial services, healthcare, and manufacturing. All types of organizations, from architectural firms to animal welfare groups, are turning to targeted search, and it’s the independent specialists who are reaping the rewards. Two firms, Cypress Group and Hill & Associates, find top talent for the wine industry.

The list goes on and on: Day schools and international schools. The sporting goods industry. Cyber security. Water and waste water. Quantitative analytics. Senior housing and senior living. Clean tech and sustainability. Museums, cultural institutions and associations. Search specialists can be found to serve each of these sectors’ needs. Even colleges retain them for athletic director openings. All of these sectors have one common denominator that’s different from mainstream corporate recruiting, say specialists working in these various fields: unique leadership needs and requirements. “It’s not enough to be successful on a traditional business level,” says Jim Zaniello of Washington, D.C.- based Vetted Solutions, who focuses on non-profits and associations. “These sector leaders need to be focused on strengthening an entire industry, profession or cause – not just one company and its individual results. As such, these individuals need to be experts in accommodating non-commercial considerations – such as consensus building, reputation management, and advancing a mission.” Men and women with those skills are a special breed, often with very different motivations and aspirations than their business world peers, he says.

For every sector, whatever the need, one seems likely to find a niche search firm standing at the ready. There is even a go-to talent solutions boutique provider to the recruiters themselves. Toronto-based Zoey Osborne is in the unique position of identifying and on-boarding executive recruiters for both large and boutique specialist search firms. Ms. Osborne spent 15 years with Heidrick & Struggles where she mastered a best-in-class internal acquisition program for the firm in North and Latin America. When the economy faltered Ms. Osborne took a leap of faith and launched Osborne Human Capital in 2012. The firm has a number of active engagements underway in New York and Chicago after a busy 24 months and it is about to launch a relationship with Caldwell Partners, one of Canada’s leading executive leadership providers.

With companies looking to become more diverse, meanwhile, a number of search firms focus on helping find qualified candidates of color. WBB McCormick, for its part, helps find professional talent from the LBGT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) community. Country clubs turn to search, too, as does the shopping center industry. Professional sports teams use recruiters to find coaches.

“We staff the church” is the motto of the Vanderbloemen Search Group. The Dallas-based recruitment provider finds pastors for churches around the country, from those with small, 100-member congregations to mega-churches with flocks in the thousands. After receiving his master in divinity from the Princeton Theological Seminary, William Vanderbloemen worked in the oil and gas industry. Following a brief tenure at another faith-based search firm, Mr. Vanderbloemen struck out on his own in 2010. With churches becoming more savvy and constantly looking for talent from outside their communities, the need for external search help was growing. Fees for pastor positions, which hover around $50,000, fall far below the amounts typically reaped by mainline search outfits. Still, Mr. Vanderbloemen and his team of 23 are faring well, taking in close to 200 assignments each year – and serving a higher purpose perhaps as well. Nor is his a staid, old school operation. Like many of the organizations of faith that they work for, Mr. Vanderbloemen and his team are facile in the ways of social media. “When I began search, Twitter was just on the horizon, and Facebook had just come into the public space,” he says. “The church latched on immediately, and I was fortunate enough to have done the same. Particularly with Twitter, church leaders have been active. Studies show that church leaders have more ‘retweets per followers’ than celebrities. As our firm has grown, our social media presence has grown. I have somewhere north of 150,000 Twitter followers alone. And the rest of the firm combined takes that number even higher. So call it the right place at the right time, good fortune, or good business. However it happened, we’ve found that social media is a huge part of our search work.”

Smaller recruiting firms often stand out over their big- firm competition by how well they know their industry and the people in it. Patricia Jacobsen Simpson is chairman and CEO of Chicago-based D.W. Simpson Global Actuarial and Analytics Recruitment. Twenty- five years ago, she helped launch the firm with her late husband, David W. Simpson – at the time they were just friends who had worked for the same general insurance company. And though business went well for the first year or so, the economy nosedived in 1990 and assignments dropped to a trickle. That turned out to be a blessing in disguise. With business slow, the pair spent their time getting to know all the actuaries they could, familiarizing themselves with their backgrounds and interests. “Now, I had already been working in actuarial recruiting for almost two years beforehand, so a lot of those relationships stayed with me as well,” says Ms. Simpson. “But we talked to 50 to 60 actuaries a day and really started building our database. When the market picked up, we had already established the backgrounds of all those actuaries.” It’s that kind of deep knowledge, combined with a thorough immersion into the various actuary organization, that separates D.W. Simpson – and boutiques in general – from larger rivals. “The biggest differentiating factor is that we get hired after they fail,” says Ms. Simpson. “And that’s happened quite a bit.”

Circumventing Off-Limits

Some highly specialized industries tend to prefer boutiques. Roberta Rea, president of Roberta Rea & Co., an Encinitas, California-based search firm, specializes in finding top talent for the shopping center industry. Having worked for a larger recruiting firm earlier in her career, Ms. Rea broke away in 1988 to serve an industry to which few firms were paying heed. “The big players like Korn Ferry were ignoring this segment of the retail sector,” she says. “I spotted an opportunity to serve a sector that needed an external recruiting partner and just went for it.” Ms. Rea feels clients responded to her on more of a partner level because she spends considerable time with them, absorbing the culture of their businesses. “I’m available for my clients 24/7 and the result is that I feel like I’m actually a part of their team. I know the candidates and their histories, too, because I’ve invested so much time working specifically for one industry.” With outlet centers like Franklin Mills on the rebound, Ms. Rea’s business is healthy; last year she completed 50 assignments as a sole practitioner.

Another advantage that small firms often have over their bigger rivals revolves around the issue of off-limits. It’s a matter that James J. Drury III, chairman and CEO of James Drury Partners, feels strongly about. Having conducted some 400 searches for more than 200 clients in practically every sector over the years, he knows the terrain as well as anyone. Mr. Drury started his career working for a boutique firm but was then recruited to join Spencer Stuart to lead a turnaround of the firm’s Chicago office. When he left Spencer Stuart in 2001, he was vice chairman of the Americas and a board director. Seventeen years with Spencer Stuart taught him a lot about the business, including the ins and outs of how big firms work. “When big companies have a big search, it’s a leap of faith to hire a small firm to do it,” Mr. Drury says. “The board sits there worrying about what happens if it gets screwed up because we hired Joe Blow Associates. Then they say, ‘Well, why didn’t you hire Heidrick? Or Russell Reynolds? “A lot of these decisions are made to protect the decision itself. It’s not to optimize the outcome, because quite frankly I think boutique firms do a much better job.”

Increasingly, Mr. Drury says, the big firms are narrowing their definition of off-limits. Or they might approach a former recruit but not necessarily present the individual as a candidate, leaving that for the client to do. And no one has forgotten how IBM, back in 1993, circumvented the off-limits protections in its search for a new CEO by hiring both Heidrick and Struggles and Spencer Stuart, so they could go after each other’s clients. “I’ve long been dismayed with the ongoing erosion of off-limits protection for clients,” Mr. Drury says. “I feel that if you’ve been privileged to get inside these companies and know them and their top team so well that you should protect their executives from being recruited away by your firm.” Remarkably few clients seem to feel equally strongly about it, he concedes. Indeed, some clients have threatened legal action and settlements have been worked out, but in large part they give search firms something of a pass. “Clients have short memories and they’re very forgiving,” Mr. Drury says.

Like any boutique owner, Daniel Kepler, who runs Cavoure in Chicago, has no problem in shootouts with pointing out the off-limits restrictions that big firms bring to the table. Smaller firms naturally have fewer such constraints, and most of them make sure potential clients are aware of the difference. At the same time, however, Mr. Kepler believes that most firms are playing by the rules in regard to off-limits. “You can get around it,” he says. “The unwritten rule is that rules are made to be broken, right? At the end of the day I think there’s very little of that.”

Building a Boutique Brand

The roads to running a boutique search firm are many. Robert J. Gariano, for one, who runs a small recruiting firm in Lake Forest, Illinois, probably would never even have entered the executive search business had it not been for a bad break. Mr. Gariano had enjoyed a successful career at General Electric and then W.W. Grainger, where as a group vice president he built a $2 billion collection of six industrial distribution businesses. He was in the running for the top job at Grainger, in fact, but came in second. As he then tried to figure out what direction his career should take, a top executive recruiter at Russell Reynolds Associates, which had recruited him for Grainger, suggested he come work for the search firm itself. Mr. Gariano resisted at first, but he finally agreed. In all, he would spend 10 years at Russell Reynolds, learning the trade, starting the firm’s successful CEO and board practices, and running its far-reaching global industrial sector.

Mr. Gariano had a good run at Russell Reynolds and still speaks well of his time there. But by 2005 he had made up his mind to start his own firm. Echoing some of the sentiments of Mr. Carpenter and others, he says that he had grown dissatisfied with the concept of leverage, the common approach at big firms (and in any number of professions) of having the senior recruiter sell the search but then pass the assignment along to a younger, less experienced associate to do the actual work. “I was very highly paid as a partner,” Mr. Gariano says. “I was bringing in a lot of business. But these clients become friends of yours after a while. And you become their trusted advisor. They put a lot of trust in you, and I found that leverage did not allow me to be as close to the process as I needed to be. If we had a search that didn’t go well, I had trouble telling my friend who I had been in business with for 10 years that in fact I didn’t actually meet the candidates, that there was a junior guy doing the search. It didn’t suit me well.” What’s more, Mr. Gariano liked the work of being a search consultant more than of being a business developer. If he had fewer people working with him and if his firm did only senior-level searches, he figured, a small outfit could do a better job of conducting searches and as a result would retain more of its clients. “I had the financial freedom that even if I failed it wasn’t the end of the world,” he says. “Secondly, I wanted to do more search assignments myself, to develop them and to do them without the leverage model being in the way.”

That’s not to say Mr. Gariano was completely at ease with what was ahead of him. Some of that stress was allayed, however, when, just two days after he left Russell Reynolds he received a late night message from the chairman of the board of a former client offering him a CEO search. He remembers billing that client and waiting for what seemed like forever for the first check to arrive. “I’ll never forget, it was a Saturday morning and my wife and I were walking the dog. She went into the post office to check our mailbox, then opened the door and came out with a smile from ear to ear. We opened that envelope and it was the first check we got. There’s nothing more exciting. It wasn’t a salary. Somebody actually paid you for what you were doing. That was just a remarkable time.”

These days, Robert Gariano Associates, which recruits senior executives and board members for public and private companies, is on a roll. “We’ve had record years each year we’ve been in business,” Mr. Gariano says. With but six employees, including four recruiters, the firm is more streamlined and can therefore be more agile than a bigger firm. “And we hold onto our clients like a diver holds onto his air hose,” says Mr. Gariano. “That’s the beginning and end of everything we do.”

For Jay Rosenzweig, president of Rosenzweig & Company in Toronto, starting his own business seemed inevitable. “I’m an entrepreneur by nature,” he says. “It’s in my blood.” But it didn’t happen right away. He started out as a lawyer but eventually joined a boutique firm, which in turn was acquired by Korn Ferry. So it was that Mr. Rosenzweig learned what he needed to know in both the big and small search environments. “The key partners from the boutique firm that I originally joined had a little bit more tenaciousness than some of the influencers at the big firms,” he says. “The hunger that entrepreneurs bring from a professional services standpoint to high end recruitment can often be superior.” Even the training he gained at the boutique was, in some ways, superior. “But the thing I will say is that having worked at the larger firms becomes a fantastic calling card from a business development perspective, because when you’re talking to a client you’re able to say that you’ve been to the big firm, you’ve had the exposure, and you’ve had the training. So if that’s something that’s important to them, you’re able to tell clients you bring the best of both worlds: we’ve been trained at the big firms and we have the exposure and now we can combine that with the kind of boutique firm rigor and tenacity that combined will yield far greater results over the long haul.”

Name Recognition

When he first started talking about starting his own firm, Mr. Rosenzweig’s advisors urged caution: “They were telling me, ‘Jay, you’re crazy. You’re a young partner at the world’s largest firm. You’ve got three kids and a mortgage. Why rock the boat? Hang in. Leverage off the brand. Leverage off the resources of the big firm. Life will be comfortable.’” But in 2004, he did walk away from Korn Ferry and started his own firm, which now employs 15 people, 10 of whom are full-time, and a number of expert partners he can turn to both in Canada and around the world. “I just felt it was the right time,” he says. “It was inevitable that I was going to ultimately try to build a business and innovate and bring something different to the table. At the same time, I wanted to build a firm that would be so deeply service-oriented that it would blow the clients away.”

One of the biggest challenges the firm faced, and to some degree continues to face, is name recognition. “Firms like Egon Zehnder and Russell Reynolds Associates have been around for a long time,” he says. “They’re well known universally and the knee- jerk reaction is to call the usual suspects when you’re doing a search. One of my big challenges was getting our name out there so that companies would think about our firm within the same breath as the bigger firms and know to call us. Our name obviously has grown and we’re known in many circles, but certainly our name isn’t as well known as Korn Ferry to this day, and we continue to fight that battle.” Mr. Rosenzweig calls the decade since he started the business “the most gratifying 10 years of my career.” Between interesting assignments, the ability to choose what clients to accept or turn away, and the financial rewards, he has no complaints — which is not to say it’s always been easy. “We’ve certainly had our ups and downs,” he says. “2008 was extremely difficult. We weathered the storm, but it wasn’t easy.”

Peter Crist, too, was urged to stay on at his big firm. He had been at Russell Reynolds Associates for 18 years in Chicago, starting out of college as a researcher and ending up as co-head of North America and a member of the firm’s executive committee. He had started thinking about retiring around 1993. The powers that be at the firm wanted him to relocate to New York, essentially to compete to someday run the business. But Mr. Crist had little interest in leaving Chicago. Beyond that, while the firm’s leaders seemed hell-bent on growth, Mr. Crist advocated scaling down and concentrating on high-end searches. He was also growing weary of management responsibilities, which took him away from what he really liked, which was doing searches. In 1995, he took the leap. One day after he left Russell Reynolds, he received a call from a former client in Kansas City. “He said, ‘We’re going to FedEx you a check tonight. We’re going to start a search and we want to be the first client you receive in your new firm.’”

Though he had no real plan when he started his own boutique, a strategy soon came to him. The Internet IPO market was starting to take shape and it quickly became apparent that there would be a big need for chief financial officers. “We got into this CFO gig before anyone else figured it out,” Mr. Crist says. “And we got lucky because the wind in our sails in that mid-90s to late-90s time frame was really strong and then it was just a matter of executing, which is what I’ve always focused on.” After four years of success, his firm was acquired by Korn Ferry. And once again he found himself working for a big firm. Among other achievements, he was vice chairman and built Korn Ferry’s board practice. But when after four years his contract ran out, Mr. Crist decided to make one more go at running a boutique. Crist | Kolder Associates was launched in 2003, with a focus on corporate boards, CEOs for small-cap and mid-cap companies, and CFOs. The firm, which employs 14 people, takes on 50 to 60 assignments a year, with a minimum fee of $200,000.

And though challenges remain, he says business has been nothing but good, even when the economy faltered. “Even troubled companies have to have CEOs and CFOs and board members, regardless of the economy,” he says. The problem, he says, is that sometimes one can get caught resource short. In other words, circumstances can cause too many assignments to land at once. And when a firm that’s built for handling four or five searches a month now has to deal with a dozen, Mr. Crist gets anxious. Clients often put a lot on the line in choosing a small specialist over the ‘safe’ big generalist and if a search goes bad, word gets out. “Quality is such a driver in our business model,” Mr. Crist says. “If you screw up a project, you become radioactive.”

Smaller firms like Crist | Kolder are also heavily dependent on its principals. Should tragedy befall one of the firm’s main players, the entire ship is at risk of sinking. At age 62, Mr. Crist finds himself perpetually busy and constantly on airplanes. “When you bump into older players in the big firms, they aren’t working hard,” he says. “But when you run into the older players in boutiques if they’re any good they’re working really hard.”

Substantial Reward

Although he might argue with the ‘older’ designation, Ken Daubenspeck, who isn’t much younger than Mr. Crist, is still working hard. He started his professional life with Electronic Data Systems, where he was a member of the facilities outsourcing transition team for its banking division. Mr. Daubenspeck was responsible for initially assessing the outsourcing client’s IT personnel to determine who would stay on and who would be replaced by EDS personnel or recruited from the outside. He recalls hiring a search firm to recruit for the technical positions, only to discover that the recruiters lacked the expertise to effectively evaluate the technical skills of the candidates. “By luck they provided me with the best candidate, who I ultimately hired, and the worst candidate, who had no qualifications at all,” he says. He finally left to get into the search business himself. “I did not enjoy the business I was in because I did not like letting people go,” he says. “When I looked at this side of the business, I saw that it was a much more positive endeavor, which is why I got into it, and because of the impact it had on people’s lives and the impact on companies if it was done well. And it was a lucrative business.” And he could create his own unique culture which is a big driver for many boutique self-starters.

Today Daubenspeck and Associates, founded in 1982, has eight employees and uses independent contractors for research. Mr. Daubenspeck is the Chicago-based firm’s only partner who sells. Recently, he collected $1.8 million for a multiple search assignment gig from an insurance company. He also does a lot of work overseas, in Saudi Arabia, Russia, and other countries. He’s busy, but the rewards have been substantial, both personally and financially. “It’s quite marvelous actually,” Mr. Daubenspeck says. “I can trust my own instincts and my own capabilities and I win or lose based on my own decisions and effectiveness. One of the reasons I never liked working in larger organizations is because you couldn’t see the parameters of the company, meaning you couldn’t tell if a company had a problem coming that was going to impact it. When you run your own organization you can see what the trends are doing to it. You can see what’s going on. And you can react accordingly.”