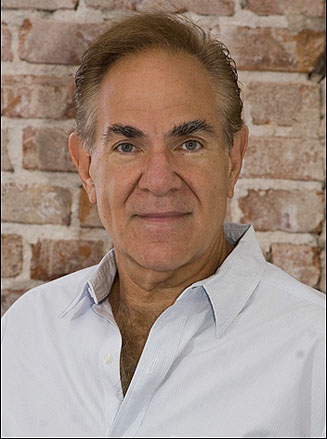

Ted Cohen’s nickname should be The Hammer.

One of the most popular speakers on the music industry's bustling conference circuit, Cohen—managing partner of TAG Strategic, and one of the pre-eminent experts in digital entertainment—can out talk, outwit, and pummel into the ground anyone dumb enough to oppose or disagree with him.

Think of a master chess player fueled up on Red Bull, and triple shots of espresso.

His four-decade digital media-fueled career has encompassed wrangling artists, as well as supervising brands, technology, and media platforms.

Music industry lore: He has more colorful stories about iconic music superstars, and industry legends than almost anyone; and his enthusiasm of music is boundless.

Music and technology: This guy practically wrote the textbook.

As EMI Music’s digital media guru from 2000-2005, Cohen created and implemented the company’s worldwide digital strategy, and led licensing negotiations with Apple/iTunes, Microsoft, RealNetworks, Rhapsody, MTV, BET, Virgin Mobile, Motorola, Nokia, Verizon and others.

As a result, EMI Music—the first major music company to make its repertoire available to digital music services—was also the first to allow listeners to download permanent copies of songs, transfer tracks to portable music players, and make copies to blank CDs.

In 1999, Cohen was practically the lone voice in the world arguing that Napster didn’t represent the death knell of the music industry.

With offices in Los Angles, New York, Miami, London, and Mumbai, TAG Strategic specializes in negotiating and expediting agreements with entertainment media rights holders.

Cohen launched TAG Strategic in 2006 with a handful of clients, including Gibson Guitar Corp., Muze, EMI Music, Limewire, EyeSpot, and Participant Media.

Since then, TAG Strategic has also worked with Coca-Cola, Verizon Communications, SanDisk, Hello Music, Stream Jam, UK Trade & Investment, Buymyplaylist.com, Emblaze Mobile, Rosenzweig & Company among many others.

Prior to joining EMI in 2000, Cohen held senior management positions at Warner Brothers Records, and Philips Media.

He also worked as a digital music/media consultant for Liquid Audio, Napster, Microsoft, Amplified, Universal Studios, Rioport, Amazon, Wherehouse Music, Dreamworks Records and music.com, among others.

He co-created the Webnoize Conference in Los Angeles in 1998, and MidemNet in 2000 in Cannes, France.

Growing up in the ‘60s in Cleveland, Ohio, Cohen managed several bands while in high school. In 1967, he began attending Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York. For two years there, he promoted shows, and worked at the school’s radio station, WICB. After receiving failing grades, in part due to his extracurricular activities, Cohen left Ithaca College in 1969. He then enrolled at John Carroll University in his hometown.

The next year, Cohen became assistant buyer at Disc Records, a 34-store national music retail chain based in Cleveland. A year later, he was hired as a local promotion rep at Columbia Records, and moved to Cincinnati.

Another year later, Cohen joined Warner Bros. Records as a regional promotion rep. Two years later, he was promoted director of East Coast artist development, and relocated to Boston.

Over the next decade, Cohen worked with Alice Cooper, the Doobie Brothers, Fleetwood Mac, the Who, Van Halen, Prince, Talking Heads, Robert Palmer, the Sex Pistols, George Benson, the Pretenders, the Ramones, Roxy Music, Asia, Al Jarreau and many others.

In 1982, Cohen joined an innovative new media work group—a cross-division co-venture between Warner Brothers Records and Atari—to gauge the impending interactions between personal computers, compact disc, and CD-ROMs on music consumers in the coming years.

In 1984, Cohen left Warner to join Westwood One Radio Networks, as head of content acquisition and tour; working on projects involving Elton John, Stevie Nicks, Foreigner and Neil Young.

A year later, he joined Sandy Gallin, Morey & Associates, a Los Angeles-based artist management firm that handled Dolly Parton, Whoopi Goldberg, the Pointer Sisters, Neil Diamond, Donny Osmond, Christopher Cross, Paul Shaffer, and America.

In 1986, Cohen co-founded Cypress Records. Its roster included Jesse Colin Young, Kenny Rankin, Southside Johnny, Wendy Waldman, John Tesh, and Jennifer Warnes.

In 1987, he began consulting Philips Media on interactive media projects for CD-i. Two years later, he joined Philips Media full-time as producer of CD-i music titles. In 1994, he was promoted VP of music at the company, leaving in 1996.

In 2000, Cohen joined EMI as VP of new media, and was subsequently promoted to SVP of global digital business development and distribution.

You seem to take a holistic approach to music and technology.

That’s pretty much it. I spent the first half of my life touring with bands. I have spent the second half of my life playing with technology that empowers music. So I get teased a lot. I have a 19-year-old son who sometimes asks if I would act at least his age. There has never been any necessity to get seriously morose about all of this. I’m still very optimistic about how all this is playing out. It’s been awkward, but it plays out nicely.

In the ‘90s, you were one of few technology experts working in the music industry.

I introduce myself to most people as the most conflicted person they are ever going to meet. In 1999, I was working for both Napster and the RIAA (The Recording Industry Association of America) at the same time. I was carrying messages back-and-forth. I was not working on the same issue. The RIAA brought me on to help figure out web casting rates. Napster brought me in to ostensibly help take them legal; although it became apparent very quickly that was not their intention. Their intention was for me to be the friendly face of the music industry working for Napster.

You participate in numerous music conferences around the world. What’s the benefit for you? Meeting clients and contracts?

In some cases yes, but I like the role of moderator, and I like the role of trying to draw people out to really talk about the issues. Last year, we did 12 salons, including in Paris, Berlin, Stockholm, and Helsinki; where we get 20-30 people together in a room with no press. (To participate) you agree that you are not going to tweet, blog or write about it (the meeting). People get incredibly candid about what the issues are in such settings. There was a guy in London, a few years ago, who said, “Nothing leaves this room.” Later, in a conversation, I asked him what was the biggest impediment in getting a deal done at his label. He said, “My boss. He’s an asshole. He wouldn’t know digital if it hit him in the ass.” I went, “Well, that was candid.” He was at the company for another year. Nobody in the room ever told his boss.

Has the gulf between the music and technology communities lessened in recent years?

It’s a bit better than it was but there’s still the promise of the big check (expected by the music industry), and that is what we need to get away from. Four years ago at MIDEM, I interviewed David Eun of Google, who is now at Samsung (as executive VP of its media-related units). I asked him, “Why are you trying to fuck the record companies over?” He basically said, “We’re not trying to fuck them over. We are trying to partner with them. We don’t want to just write them a big check. It’s not a vendor/supplier relationship. It’s a partnership. If the labels get their heads out of their asses, they are going to make more money from Google than ever. If they stop looking at the size of what the advance check is.”

Label executives fear a re-run of the MTV scenario where a company is built on their backs.

I don’t see that (fear) alleviating in the near future. The labels are still concerned that fortunes are being built (on their backs). There has always been (the attitude), “We will get a big check from Google or Apple” or from wherever. Looking out at the horizon, I don’t see who the next big check is. Labels should be more focused on considering what long-term partnership can generate significant revenue as opposed to who has the biggest checkbook that can help them make the quarter.

Are labels and others missing opportunities? Leaving money on the table?

My biggest current frustration. We had a client last year, Ovation Towers in Los Angeles headed by Ian Murray. He’s a lovely guy struggling with one of the best ideas ever. I had met him at a bunch of concerts and events. He kept saying he had something he wanted to bring to me. Finally, I sat down with him, “Okay lay it out for me.”

What has he come up with?

He has come up with a very efficient live recording process where he records on two Pro Tool rigs. The minute the band finishes the first song, the next song is recorded on rig number two, and the first song is indexed. He has five 42” screens mounted vertically forming a video wall to merchandise the fact that the show you are seeing tonight, you can purchase on your way out the door. Or you can purchase it now and just plug your iPhone in as you leave.

The resistance from labels, from managers, and from artists to having their band—not recorded live because they are being recorded live every night by everybody in the audience—but being recorded with a decent quality recording that a fan could buy for $10 or $15 was incredible. They all said that they didn’t want to do recordings. I said, “Are you watching the audience? Everybody in the audience is holding up their iPhones the entire evening. This isn’t 10 years ago, you idiots.” I swear to God, every manager, every agent, and every record label said, “No we don’t want the shows recorded.“

But these live shows are being recorded by fans.

My biggest frustration in the last six years has been that of the push back and of the money being left on the table by not monetizing things like this. They aren’t stopping anybody recording shows. All they are doing is leaving money on the table.

In 2006, you founded TAG Strategic. Has the focus of the company changed over the years?

It’s challenging on a daily basis because the most interesting companies to work with are the ones least funded. So what we have to do continually is come up with a balance of companies that are really good companies to work. For example, we have worked with SanDisk, Motorola, Gibson, Verizon, and Coca-Cola. They have all been really good clients with market level retainers.

Your company continually gets pitched to represent new companies. You sometimes crash peoples’ dreams.

If there’s anything that continually amazes me is how talented some of these people are but, at the same time, they are so single-minded about what they are doing that they are not aware that there are three other people doing what they do. Maybe not as well as them. People will come in, and the one thing that we will usually be able to throw a large rock at is (the claim), “We are the only people doing this.” “No, you’re not. What about so and so?” “Who are they?” “Well, let me show you.” The reaction usually is, “Oh my God, they are doing what we are doing.”

People with such startups don’t generally come in educated about the marketplace?

No, they don’t. We try to explain everything to them. If we are trying to explain “TAG For Dummies,” we say that we are the finishing school for start-ups. We take people who have a core natural or raw talent. They will come in, and say, “We have a great product.”

How do you react?

We might say, “It’s not a product yet. You have a technology or a process, but you haven’t productized. It is not consumer facing. I know that your engineer friends like it, but it’s not ready for the mass public. You haven’t come up with a real business model. If you are basing the business model on the idea that the entertainment industry is going to pay you for this, you are going to be in a lot of trouble. If you based it on, ‘we’re going to show this to a record company or a film company or television network, and they are going to pay us for this, that’s 5% of the time. The other 95% of the time, it’s Samsung paying for it. It’s Coca-Cola paying for it. It is somebody else who has decided to sponsor or fund it. If you are thinking you are going to walk into Sony Music, and show it to the digital guys there who will say, ‘Go talk to our marketing guys. They are going to pay you thousands of dollars a month,’ it’s not going to happen.”

Can today’s artists reach audiences to the same degree as artists in the past?

Here’s the biggest problem. There used to be a bit of a difference between really good bands, and bad bands. The level of musicianship has really gotten better. A band that you would have thought was a great band 10 years ago is (today) a really good band. To stand out against the amount of competition, and the amount of dedication that some of these musicians have, a band can’t just be really good. They have to be monumental. It really has to be life-changing. And there aren’t that many of those.

I used to say that the good thing about the digital age is that you have a level playing field. The bad thing about the digital age is that there’s this incredibly level playing field where there are hundreds of thousands of people competing for my attention.

YouTube has become the biggest radio station in the world.

Absolutely. YouTube is the most successful music service in the world. Forget everybody else. The barrier to breaking through to success is higher than ever. But, if you have that Justin Bieber moment, you can. From my perspective, everything that I’ve read, this was just a stage mother, and a very dedicated kid.

[Manager Scooter Braun famously discovered Justin Bieber in 2007 through videos that Bieber and his mother Pattie Mallette had posted on YouTube. Braun tracked down the Biebers in Stratford, Ontario, and convinced them to fly to Atlanta for a meeting. He then signed Bieber, who had just turned 13, to a management deal.

After further YouTube videos, and after building up an online presence, Bieber signed a multi-rights deal with Raymond Braun Music Group, which was created specifically for him. Chairman and CEO of Island Def Jam Music Group L.A. Reid, in turn, inked Bieber to a 50/50 joint venture with Island Def Jam Music Group in 2008.]

Justin apparently has a 360 deal, which you favor because the revenue just isn’t there for a label without having other income streams.

Yeah. When, in the current economic structure, people expect labels to spend the kind of monies they spent 15 years ago—with no promise of any significant return—it has to be across multiple revenue streams. When I was on the label side, it was like, “Why are you rooting for the other (artist) side?” Now it’s, “Why are you rooting for the label side?” One of the guys in one of the business schools once said, “It may not be the best deal for either side, but you know that a deal is going to be successful if you’re told, ‘You are going to negotiate a deal, and you don’t know what side you are negotiating for.’”

As much as people say that artists don’t need a label due to the internet, many do.

Right. Even if they cobble together everything that a label does. It’s a combination of having a label—or at least a good hub at the top of it (the team)—and, then maybe, you customize the spokes.

With the cloud music space being so crowded with Google, Apple, Amazon and others, is there synergy between the file hosting service Dropbox and Audiogalaxy, the music hosting and streaming service in a deal that was recently announced?

It’s a really good moment. But if you look back to 2001, David Pakman had MyPlay (pioneer of the digital music locker), and Michael Dowling had Music Bank. In 2001, I did a $1 million deal with Music Bank to provide cloud storage of all your music. That was in 2001. Then in 2011, everybody was talking, about the cloud like it was a novel idea. It takes the Googles, the Apples, and Microsofts to mainstream an idea and make it consumer friendly. Then it becomes an interesting opportunity.

Do you still favor subscription over advertising-based music services?

Yes, I do. I don’t think that the advertising model so far has proved to be sustainable. I think that we have undervalued subscription. I am paying $150 a month for cable. I watch 20 or 30 hours of TV a week. I probably listen to 50 to 60 hours of music a week. I’d argue with you that music is worth more than $10 a month subscription service.

The labels were so concerned about (piracy)—and I was there at the time—that we had to come up with a price that was just a little bit more than free to convince people that they should pay. So far, we have not been able to raise the price. I think that music is worth at least $20 or $25 a month.

People generally don’t even know what music they are listening to while watching TV. If a viewer could be presented with the opportunity to buy the music they are listening to while a show is being played, they would be more likely to make a purchase of a particular track.

Right. There are some tools coming out to deal with that.

[Audible Magic's automated content recognition system can currently identify a song. Audible Magic is working with television set and set-top box manufacturers to integrate options into their hardware.]

Of course, Shazam recognizes songs.

Yeah. Shazam is a DVR technology. “Law & Order” recently had a song that started really low underneath (the spoken word credits) “In the criminal justice system.” I really loved the song, but I didn’t recognize the artist. So I ran it back, turned on Shazam, and it popped up that it was James Blunt’s "I'll Take Everything. It was the first time that I’ve seen “Law & Order” use a piece of music as a thread throughout an episode. Anyway, I had to use the DVR to go back. In real time, I would never have been able to do that. So there’s got to be a better way to do that.

The buzz phrase in the music industry today is “data is king.” Certainly, data has become a hugely valuable commodity as companies seek ways of making money from users' web habits. Can people now fully gauge this data? Do they really know what it is?

It all comes down to having a really good dashboard. When SoundScan came out (in 1991), it was really hard for people to wrap their heads around SoundScan. When you (as a label executive or as a manager) had to go to someone in IT to pull a report for you. When there wasn’t a front end on there to let you look at it, and be able to slice and dice it. Somebody had to deliver a finished report to you. You couldn’t look at it (a report) and say, “Okay. I got it. Let me look at this from this angle.” You had to call back down to IT, and say, “Okay, run me another report.” It all comes down to providing a great dashboard.

You know things like Next Big Sound with (CEO) Alex White (launched in 2009); his big win was having a dashboard within two or three minutes. You are sitting there going, “What about this? What about if I compare this market to that market or this artist to that artist.” It’s the ability to manipulate that data. If you can’t harness it, it’s no use to you.

[Next Big Sound measures the growth and popularity of bands across social networks, streaming services and radio.]

It’s becoming all about evaluating direct engagement with fans via social networking.

What is the engagement? What is the length of engagement? What is happening after the engagement?

While at EMI, you argued that the music industry should try to benefit from data being derived from peer-to-peer piracy. BigChampagne was then monitoring P2Ps networks. In hindsight, the music industry should have been studying this data instead of shunning it. The industry lost a decade of music fan data it could have been tapping into.

Absolutely. BigChampagne is a great example. When (co-founders) Eric Garland and Joel Fleischer showed me BigChampagne I thought it was phenomenal in terms of the ability to see what people were interested in. The push back, at EMI and at other labels, was, “We are validating piracy. By recognizing what people are doing, we are validating their illegal activities if we are quoting their habits.” Eric pointed out very succinctly, and very eloquently at one time that, “When a label says that nobody is pirating a particular artist’s music, the label should be worried because if the fans aren’t trying to steal it (the music) they are definitely not going to buy it.”

[BigChampagne, opened for business in 2000, tracking the two basic activities that could be monitored on peer-to-peer networks: "queries," or searches, and "acquisitions," or downloads. Then they were able match a computer's IP address to its zip code, creating a map of P2P activity.]

The music industry was then very nervous about the conversion of CDs to music files.

Absolutely. It (the music industry) was a bit myopic. The labels should have figured out a way to engage with Napster. But, at the same time Napster, really did not want to engage in a meaningful way. They wanted to stall. They had this strategy or theory called, “The Congressman’s Daughter.” If the congressman’s daughter was using Napster at home, and she showed it to dad, who was a congressman or a senator, he’d go, “Wow this is really cool. Do they have Frank Sinatra?” And copyright law would suddenly be— not irrelevant—but dated, and would get changed.

How did you come to consult Napster in 1999?

I got an email from a friend of mine saying. “Check this out.” It was a link to Napster. I went to Napster, and I went, "Oh my God.” There was a box on the site that said that if you are interested in advertising click here. I clicked on the box, and said who I was, and what I did.

About a week later, I got an email from (Napster co-founder) John Fanning saying that he wanted to talk to me. Quite honestly, I dropped the ball. I didn’t get back to him right away.

In September ’99, I was in JFK (airport) flying to Stockholm, and John Fanning called saying he wanted me to come to San Mateo (California) to meet with them. I come back from Sweden, and fly up to San Mateo. I get driven to the San Mateo Bank Building where Napster was. I get off the elevator, and I go around to the office that says “Napster.” I open the door, and there sleeping on the floor, using a motorcycle helmet as a pillow, is (Napster founder) Shawn Fanning. I didn’t know it was him. I wake him up because it’s 8 A.M. and I introduce myself. He doesn’t get up. He just puts his hand up and we shake hands. He says, “They will be here in a couple of minutes. We’re going to have coffee with them.”

Shortly afterwards, Eileen Richardson (Napster's interim CEO) and (Napster investor) Bill Bales showed up, and we go down the street to Starbucks. They say, “So we talked to John. When can you start?” I said, “Today.” They asked if I had other obligations. I asked “What are you talking about?” They said, “Well, you are the new CEO.” I said, “John never told me that. I think I’m coming here to consult for you. Can we date for awhile?”

So you start consulting Napster?

I go up there a couple of times. They ask, “What labels should we approach?” I said that, “My friend Jay Samit at EMI (then EVP of New Media), I think that he would get this.” So Bill and I went to see Jay who said, “Come back to me with a proposal.” We leave the building, and get in the car. I said, “So we have to write a proposal.” Bill said something like, “We’re not going to do a proposal. We are going to keep talking to him. We are going to stall him. We have hired a lobbyist. We are going to be able to change copyright law. File sharing is going to become legal.” I said, “It’s never going to happen.”

So they had no real intention of Napster being a legal music service.

They were sending me emails during this time asking if I would take the CEO job. They gave me shares in Napster for consulting. A retainer. I went up for one meeting, and in the conference room there was a white board with all of these talking points. "If the press calls, and asks, ‘Do you realize that this is illegal?’ Tell them, ‘We didn’t think so.’” And, "If they ask if we are trying to work with the labels, assure them, ‘Yes, absolutely, we are.’” It was all how to deflect any question. I said, “This is all a big stall, isn’t it?” They said, “We think we can win in court, and we think that we can win in the court of public opinion. There will be such pressure.”

While Napster never developed a true business plan or a viable revenue stream, it exploded from 150,000 users in 1999 to more than 70 million users two years later. I remember Shawn Fanning being on the front cover of Time magazine.

No one had ever seen anything like Napster before. At the time, I was trying to tell my wife, “Please stop downloading music.”

Within the next year, you came to EMI as VP of new media.

Right. Here’s what happened. In January, 2000 I was consulting Liquid Audio, Rioport, Amplified, Wherehouse Music, the RIAA, Napster and others. I had between 20 and 25 clients under the company, Ted Cohen Management/Consulting Adults. Jay Samit hires me to put to put on a new media conference. I had done Webnoize Conference in Los Angeles in 1998 in ’99, which had done $2 million in gross revenues for a three day event at the Century Plaza. Jay asked if I could put on a private event for EMI. Basically, Webnoize but just for EMI. I said, “yes.” He asked if I could monetize, it and I said “yes” very quickly.

Why say yes so quickly?

It was, “If you are Microsoft do you want to fly around the world and meet every EMI in every territory or come to Atlanta for three days and hang out with the entire company? Doesn’t it make more sense to spend three days in Atlanta in a social and immersed setting? By the way dinner is going to cost you $25,000.”

I ended up raising $300,000 for this conference in Atlanta in May, 2000. I fly to Atlanta and I walk into the bar at the Ritz-Carlton at Buckhead, and one of my clients Frazier Hollis (EVP of) Amplified.com is sitting with Jay Samit who says, “Ted, why don’t you tell me what you are up to?” He hands me the conference program that says, “EMI New Media Staff: Jay Samit, Senior Vice President; Ted Cohen, Vice President of New Media." I ask, “What’s going on?” Frazier leaves, and Jay says, “I told you a year ago that I needed you here.”

He had tried to recruit you to EMI a year earlier.

I had said, “I have 25 clients that are paying me a really good retainer, you could never afford me.” He now says, “I’ve got it all worked out. We are going to let you keep your company. You’ve got to get somebody else to run it day-to-day. You have recluses yourself if one of your clients comes in to do a deal.”

Of course, Jay would become EMI’s global president of digital distribution.

Jay had been put in a position by Ken Berry (head of EMI's recorded music division until his departure in 2001) to reinvent EMI from a digital perspective. There was this (strategy) there that as long as there was a reasonable revenue stream—the promise of a reasonable revenue stream—try anything. It only took three signatures to get a deal done. Jay would sign it. It would get sent to Ken Berry who would look at it, and sign it and he would send it to Tony Bates who was the global CFO. As long as Tony thought that the numbers looked reasonable, every deal got done. It was a very eloquent pipeline at the time.

[In 2001, Jay Samit was quoted in Forbes magazine, saying, "My job is to make buying music easier than stealing it. It's faster and easier to rob a liquor store than it is to build a grocery store, which is what we're doing."]

In the early ‘70s, you were a regional promotion rep in Ohio for Columbia Records, and later Warner Brothers Records.

I was at Columbia, which led to Warner Bros. Records. How I ended up being director of artist development (at Warner) was that every band that came to my region I ended up running away with them. After doing that for three years, Warners put me into artist development. I was calling in from Chicago or New York saying, “I got on Alice Cooper’s plane and they told me to go with them.”

On the first night of a tour with Van Halen, the band emptied your hotel room of furniture.

An absolute true story. “Van Halen II” (1979) is dedicated to The Sheraton in Madison, Wisconsin, which was their hotel the first night of the tour.

So you figure Valerie Bertinelli is another Yoko Ono?

Oh you saw that (in an article on the internet). We got into a Twitter war after it. I haven’t seen her in years, but we got into a Twitter war. My room faced the marquee of the Aladdin Hotel (in Las Vegas). They were taking down the old marquee and putting up the new marquee because Wayne Newton had bought The Aladdin. I’m sitting there with Eddie who says, “I have made a terrible mistake.” This was right after he got married. He came into my room at 3 A.M. I think that he left at 7 A.M. We just sat and drank, and talked about how unhappy he was.

[Eddie Van Halen, and actress Valerie Bertinelli wed on April 11, 1981. In 2005, Bertinelli filed for divorce, which was finalized in 2007].

You were at Warner Brothers Records from 1974 to 1984. A golden musical age for the company.

(In artist development) we were an extension of the artist at the label. We sometimes got questioned internally about what side we were on. This was a schizophrenic environment to be in because we wanted to see the artist succeed and other people in the company had a different view.

But there were no politics there.

(Early on) I went to Bob Regehr, (senior VP of artist development and publicity at Warner Brothers Records) and asked, “What’s the approval process if I want to do something?” He said, “Well, there is no approval process. I hired you to do what I think that you can do. Keep doing good things, and you are going to be here for a long time.”

So in 1983, I was sitting with Ken Cody from “The Source.” He said, “We want to do Roxy Music live at the Radio City Music Hall (in New York City). This is during the “Avalon” tour. He said that it’d cost $40,000. I said, “Okay.” He asked, “Can you get it approved.” I say, “I just said okay. We’ll do it.” (Recorded on May 26, 1983) it was one of the most successful broadcasts of that time period. It (that corporate freedom) screwed me up for the rest of my life because when I went to work for Phillips someone would say, “Who did you ask?” That became challenging.

One of the things I got to do at Warners was that I ran the Warner Brothers Music Show. The monthly discs of the (promotional) discs in the red jackets. I did Dire Straits in San Francisco, Van Morrison at The Roxy (in L.A.), and the Pretenders recording in Boston, Philadelphia and Washington. We also recorded Jimmy Cliff, Talking Heads, and Robert Palmer live.

Any downside to working at Warners?

The one thing that bothered me at Warners was that we were embarrassed by commercial success. Warners was such a cool label that Shaun Cassidy was an embarrassment. Bonnie Raitt’s success was great success. Little Feat’s success was amazing success. Al Jarreau’s success was too. But if we had a Shaun Cassidy record, we were embarrassed by it. It was like, “Fine, we’ll take it.”

Shaun Cassidy’s successes paid for another dozen records.

Exactly.

To many people in the music industry are too hip for the room.

Yeah. While working Disc Records (in the early ‘70s), one day this manic guy walks in. I’m the assistant buyer for 34 stores across the country. It’s my first real job. This guy comes in and we talk. Two days later comes a letter from Chicago saying, “Great meeting you. Looking forward to getting together with you again.” It was signed “Neil Bogart” (then running Buddah Records, the "bubblegum pop" music label). It was on Buddah Record’s pink stationary.

Today, I’m on the Board of directors for the Neil Bogart Memorial Fund. When I first got on it, I showed the letter to (Neil’s widow) Joyce to say that meeting her husband at the beginning of my career meant a lot to me.

On the hip scale, you are credited with Todd Rundgren landing on Billboard’s Top 10 chart.

In 1972, Todd came out with the (double album) “Something/Anything?” The first single was “I Saw The Light” which was a hit (reaching #16 on the Billboard Hot 100). The album sold 75,000 units, and that was that. I called Paul Fishkin who was running Bearsville Records (as president) for Albert Grossman from Cincinnati. I said, “I’ve been listening to a track on side three called “Hello It’s Me,” and it’s a hit. He says, “Yeah but it was a hit (separately in both 1969 and 1970) by Nazz,” Todd’s earlier band. I said, “I know. I have the Nazz albums. This version is a huge hit.” He then said, “Let me talk to your bosses.” He came back, and said, “Nobody thinks it’s a hit. You are the only person.” I said, “Give me 1,000 singles.”

For the next six months, I worked radio. I went to Brian McEntire at WCOL in Columbus, Ron Vance at WING in Dayton, and Robin Mitchell, the PD at WSAI saying, “Please play this record. I’m telling you that it’s a hit.” A year and a half later, it was a Top 5 record. We broke it out of the midwest. I got the other promotion guys in the regions to go to their stations. We ended up selling a million records. Albert Grossman gave me a Todd Rundgren concert as a present. I took that money (as a co-promoter), and bought Sony U-Matic 3/4-inch video-cassette recorder.

Very cool at the time, for sure.

In 1974, I was carrying this Sony 3/4 inch U-matric video machine on the road. Four years before Beta and VHS. I would say to a girl backstage in Philadelphia, “Would you like to come up to the room, and watch Van Morrison in concert?” So I met girls. It was like I was showing them fire. “Where’s that (image) coming from?” “It comes out of that box.” “Is it being broadcast?” “No, it’s coming off of a tape. “What you mean?”

In 1977, you went to the CES (Consumer Electronics Show) convention in Chicago. It was the year that Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak showed up with the legendary Apple-1 computer.

I am at Warners doing artist development. I was living in Boston, and I met the people from Advent Corporation who did the first big-screen TV (the Advent VideoBeam 1000). I had this thing between me and stereo companies where I would send them music to send out to their stores to play to demo their speakers and turntables. They said, “Why don’t you come to CES with us?” So I go with them in ’77. They are staying at The Drake Hotel. So we are sitting in (Advent president) Peter Sprague’s suite, and in walks Steve and Steve with an Apple-1 under their arm in a brown canvas zipper case. They say, “This is a personal computer. It’s the first computer that can display color graphics on a TV set.” They wanted a trade, which we did. We traded them an Apple-1 for an Advent Video Beam.

[Apple was established in 1976 by Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne to sell the Apple-1 personal computer kit. They were hand-built by Wozniak, and first shown to the public at the Homebrew Computer Club. The Apple-1 went on sale in July 1976, and was market-priced at $666.66.]

A few months later when I got my own VideoBeam from Advent, they came over to the house for a video party. I was showing Fleetwood Mac videos, and they said, “We are going to be doing an ad in the 10th anniversary of Rolling Stone. We want you to be in the ad.”

[The Advent ad with Cohen in pajamas ran with the headline, “I used to sleep until noon. But since I bought the Beam I get up at eight o’clock to watch Tom and Jerry.” Check it out at: http://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2010/09/ted-cohen-as-a-pajama-model-circa-1997-.html ]

Atari was acquired by Warner Communications in 1976. Your first computer was an Atari.

My first computer was an Atari 800 with a 300 baud Hayes Smartmodem. I met the Atari folks and started hanging out with them. Basically, we had started an inter-company synergy committee. (Warner Bros. Records executive VP) Stan Cornyn put me on it. I was the representative to this committee. So I met the Atari folks. They set me up with a computer.

You grew up in Cleveland hanging around the set of “The Mike Douglas Show.” Did you hang around the set of “Upbeat,” the syndicated music variety show produced at WEWS-TV.

Yep with (host) Don Webster. Walt Maskey booked the show. Herman Spero began a rock and roll dance program called "The Big Five Show" in 1964, bringing Don Webster in from Canada as host. It went into national syndication as "The Upbeat Show." I went to elementary school with his sons, David and Harry Spero at Moreland School in Shaker Heights, and then reconnected with them in high school. David managed Joe Walsh for years, and has managed Cat Stevens (Yusuf Islam), and Don Felder.

Many of the acts that came to Cleveland for “Upbeat” also played locally at the same time.

Walt Maskey saw the opportunity to exploit the talent he booked by featuring them at the multiple venues he was running, Maple Heights VFW, Painsville Armory, and Chagrin Armory, among others. “I’ve got all of these bands coming to Cleveland. Why don’t I have them come in on Friday? I’ll take them around to two or three national guard armories and VFW halls.” Then the bands would do the show on Saturday afternoon and we would take them around to three more venues. While I was a junior in high school, I got paid to do promotion for the Chagrin Armory. To put fliers on cars at different high schools.

You managed bands in high school as well

I managed Eric Carmen’s band, the Sounds of Silence (which broke up in the summer of 1967, while in high school. Then I managed the Rebel Kind. Later on, Eric Carmen and (keyboardist) Kenny Margolis joined the Choir.

Cleveland had some great bands back then, including the Mods, the Lost Soul, and Silk with Michael Stanley.

This is stuff I am so passionate about. In high school, I did all this promotion. I worked at the radio station KYW in Cleveland on the weekend.

KYW was where Jim Gallant was.

Yep, Jim Gallant and (future wife) Mary Ann Moir who was Mike Douglas’ secretary. I used to go in on Saturday nights, and answer phones for Jim Gallant. “This week, it’s the Four Seasons versus the Beatles.”

A weekly Battle of the Bands.

The Battle of the Bands every Saturday night. That was my junior anode senior year in high school. I did that on Saturday nights. On Friday nights, I was at the Chagrin Armory promoting shows.

Meanwhile, you were hanging around “The Mike Douglas Show” meeting the Beach Boys and the Byrds.

The Byrds, Chad & Jeremy, Eric Burdon and so many others. Mary Ann would call my mother up, and say, “We have Peter & Gordon on this week. Let Ted know if he’d like to come down. Depending on what time of the year it was, I would either go down or skip school and go down.]

How did you score Beatle tickets for their 1964 and 1965 appearances in Cleveland?

My mother put on parties for society people. My mother was really creative. She wasn’t a caterer. Before the concept of a party planner, she was a party planner. She would do events at the Beechmont Country Club and the Oakwood Country Club working with $200,000 budgets. For “An Evening in New Orleans,” she would fly up jazz trios from the French Quarter. She would have food flown up. I remember that once she had food flown up on a TWA flight at 4 o’clock. It landed at the (Cleveland) airport at 6 o’clock, and it was delivered hot to the country club. My mother became friends with the owner of Tyson Tickets because she would get tickets for some of her clients. So we had Beatles tickets. We had Simon & Garfunkel, and Rascals’ tickets.

What did your dad do?

My father was in the dry cleaning business. My mother gave me a creative ethic and my father gave me a work ethic. My father would go at 5:30 every morning and turn the boiler on. Even though he had a bunch of people working for him.

Were you the “music guy” at high school?

I was the “crossover” guy. I played football. I wrestled. I was good in physics. I wasn’t involved in a particular group. Music was the defining thing for me, and it crossed over a bunch of cliques.

In 1967, you began attending Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York.

I applied to Ithaca in pre-med. I’m there maybe two weeks, and someone asked, “Are you going to the Rod Sterling event?” Rod Sterling was a professor there. He lived up on Lake Cayuga, and taught broadcast writing at Ithaca. This was at the height of “Twilight Zone.” He shows “An Incident At Owl Creek Bridge” (also known as "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge" and “La rivière du hibou,”) which was the only “Twilight Zone” (episode) that wasn’t done by Rod Sterling. It was done by a French company. So I meet Rod Sterling, and I am invited to one these coffee sessions at the Athens Restaurant where I met another professor. I told him about Mike Douglas and the other things I had been doing, and he said, “What are you doing in pre-med? You need to be in the broadcast department.” So he got me transferred over.

[“La rivière du hibou,” directed by Robert Enrico and produced by Marcel Ichac and Paul de Roubaix, was released in 1963. Filmed in black and white, it won the award for best short subject at the 1962 Cannes film festival, and the 1963 Academy Awards. In 1964, it aired as an episode of the Rod Sterling anthology series on CBS-TV, “The Twilight Zone.”]

Were you working at WICB at the time?

Yeah. I was doing WICB. I was doing overnights on the weekend. I also ended up working for (TV host) Gary Moore’s son, TG Morfit. They had a company called Mnorx with two clubs, The Boxcar, and this big club called The Warehouse. They hired me for the weekends to drive to Elmira, Syracuse Oneonta, Keuka, and Buffalo. Bands would send either a reel-to-reel tape or a letter saying that they wanted to play at their clubs. They would send me out to see the bands. If I recommended them, they were hired.

Two years later, you left Ithaca College because of failing grades.

At the end of my sophomore year, I was working at the radio station, and working for The Warehouse. I am now a broadcast major. I’m taking advertising broadcast writing. One professor said, “You have been basically able to juggle things, haven’t you? I think it’s time for you to stop juggling for a while. If I give you a C, you stay in school this fall. If I give you a D, you are out for a semester. I think you need to take a semester off.” He basically said, “I’m going to teach you a lesson.” He gave me a D.

What then happened?

I was put on academic probation; and sent back to Cleveland. I go over to John Carroll University, which is like a mile from my parent’s home. I walk into the administration office, and I tell this guy what happened. I goofed up. I flunked out of school. “But let me get my professor Don Woodman on the phone.” I get Don on the phone, and he says, “Ted’s really good. We want him back next semester.” I had a full course load at John Carroll as a transit student. So I was taking full credits. Two weeks after I get there I find out that there is a campus radio station in the Bell Tower, WJCU. I started working in the radio station, and everything is going okay. Then my mother who is a very histrionic Jewish mother says, “You are going to screw this up again. You need to quit the radio station. If you don’t quit the radio station, you have to leave home.” So I went, “Fine. I am out of here.” I left.

You were 18 or 19 and had to take care of yourself on your own.

I grew up in the dry cleaning business. I would get up in the morning, and get dressed for going to school. I would come home for lunch, and change clothes. I would come back from school, and change clothes to go outside and play, and then change clothes. I’d have dinner, and take my clothes off to go to bed. The next morning I’d put the clothes at the back door for my father to take to the dry cleaning.

All of a sudden, I leave home and I’m wearing the same clothes for three or four days. You want to talk about a future shock. I’m worried that my shirt has something growing on it. I’m going to friend’s rooms to take showers and do laundry. It was hilarious.

How did you survive after leaving college?

My first paying job was working at a Village Voice type newspaper. I wrote record reviews, and sold advertising. Then I then went to work for a chain of 34 stores (Disc Records) as an assistant buyer. Because I had never worked in a record store, every Saturday morning I went to one of our stores, and worked behind the counter for free. I did that for almost a year.

I lucked out. It happened that was the year (1970) of Elton John’s first album ("Elton John”), James Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James,” Cat Stevens’ “Tea For The Tillerman,” the first Emerson, Lake & Palmer album (“Emerson, Lake & Palmer”), and the Stephen Stills solo album (“Stephen Stills”).

I could find an album every week that, if you walked into the store, I could find something, and say to you, “Larry, buy this record. You are going to love it. If you don’t love it, I’m back here next Saturday and bring it back. I will buy it back from you, personally.”

An unexpected U-turn in your career was working in artist management at Sandy Gallin, Morey & Associates in 1985.

Sandy changed my life in that when I was at Warners, if you called me, I would call you back as soon as I could. If you didn’t call me back, I called you again. If you didn’t call back; not my problem. But I did return your call. When I went to work with Sandy, he’d say to me, “Did you get a hold of Larry in Canada?” I’d say, “Yeah, I left him a message.” “I didn’t ask you if you left him a message. Did you get a hold of him? Did you get the deal signed? Did you get the check? Is the check in the bank? Did the check clear?”

With Sandy, it’s about seeking an end result. Not about covering your ass.

That was the thing. I learned the difference between covering my ass, and getting it (a task) done. As much as I hated working for him—I was only there nine months, and it was the longest nine months of my life—I learned how important it is not to look at what the task at hand is but what the goal is on the other end. I think about him screaming at me from time to time. It made the difference in my life in really getting things done.

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining Celebrity Access in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-89. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record. He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide.”

LeBlanc, the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry, will be honored at the 2013 Juno Gala Dinner & Awards on April 20th in Regina, Saskatchewan.

Ted Cohen